Almack’s Assembly Rooms. That bastion and beacon of the haute to. Moreover, it was one of the first London clubs that admitted both men and women.

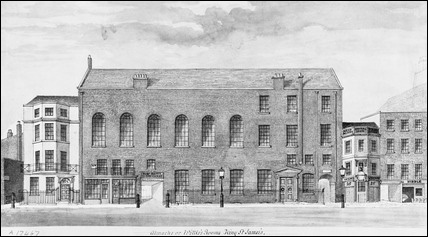

Opened Feb. 20, 1756 on King Street in St. James, exclusivity of the club was managed by the six or seven Lady Patronesses, who gave non-transferrable annual vouchers to those who could pass the social muster. Younger sons, for insistence, would not oft be admitted, nor would high ranking debutantes with even a whisper of scandal attached to their name. The Patronesses adhered to strict rules in an effort to present the cream of the crop on the marriage mart.

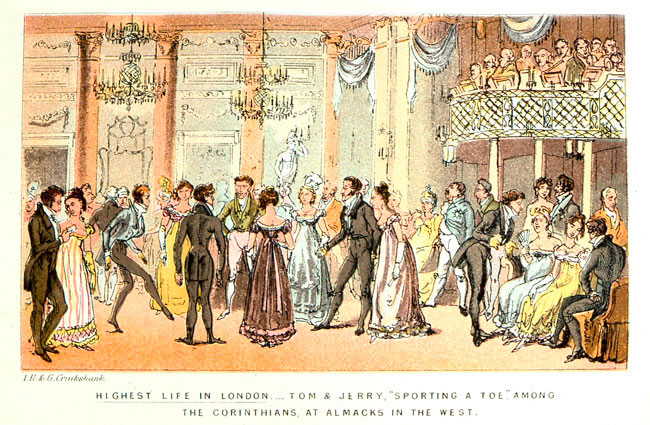

Every Wednesday night during the Season (second week in April until the middle of July), select ton could attend Almack’s ball which provided a supper to distinguish itself from other ton balls. Supper was served at 11pm, when the doors closed for admittance. Then, gambling and dancing would last the rest of the evening.

Gentlemen found Almack’s a chore, because it was a dry establishment and only served tea and lemonade, and moreover, they were required to adhere to a strict dress code of knee breeches and white cravats (the Corinthians and dandies shuddered in horror, I am sure!).

“Almacks or Willis’s Rooms” c1800. Artist unknown. Image courtesy of the Museum of London.

Almack’s consisted of three rooms, one the Great Room which was one hundred feet long by forty feet wide.

During the hey dey of the Regency the Lady Patronesses were: Princess Lieven (Russian), the Countess of Jersey, the Marchioness of Londonderry, Lady Cowper, the Countess of Brownlow, Lady Willoughby D’Eresby, and the Countess of Euston.

Here is a fabulous contemporary of the Patronesses James Grant, writing in The Metropolis:

“Miss Manchester applied at the beginning of last season for a ticket. ” Who is this Miss Manchester ?” inquired Lady Dominant. “Does anybody know anything about her? I never heard the name before.”

“Nor I,” said the Marchioness of Duffus,” Some upstart vulgar creature of city origin, I suppose,” she continued, giving her head a most contemptuous toss.

“She is a very respectable young lady; I have seen her two or three times, and she is possessed of an immense fortune,” said Baroness Positive.

“Made, I have no doubt, by her father’s spinning-jennies,” said Lady Dominant, sneeringly.

“Her father is a manufacturer in the Manchester trade, but he is a most respectable man: my brother and he are on very intimate terms,” said the Baroness.

[-14-] “Well, surely the impudence of these low-bred, vulgar people! it exceeds everything,” said the Countess of Speyside. ” Why, after this, it would not surprise me to see every coal-merchant’s daughter in the city applying for admission.

“O! the very idea of the thing is monstrous,” observed Lady Rafford. “Besides, the creature’s a perfect fright. You know, my dear Baroness, you pointed her out to tee one day in the Strand.”

“Quite a turnip face, I dare say,” said Lady Dominant.

“And cats’s-eyes, I’ll answer for it,” observed the Marchioness.

“You are both right,” said Lady Rafford.

“And you might have added carroty-hair. The very thought of such a horrid-looking creature, and a cotton-merchant’s daughter, waltzing at Almack’s, almost throws me into hysterics.”

“I think you are unreasonably severe,” observed the Baroness. “She is heiress to a princely fortune. Her father is worth half-a-million, [-15-] and her hand would therefore be deemed a prize by any nobleman in the land. My brother, Colonel Vincent, has begged of me as a particular favour, to do all I can to get her admitted, and I therefore hope your ladyships will give her a voucher.”

“Yes,” said Lady Dominant, bridling up, yes, if we wish to disgrace ourselves and the order to which we belong. If we did, I dare say,” – she continued, biting her lip and tossing her head, “I dare say the piece of vulgarity would come to our balls dressed in some of her father’s cotton-cloth. Better admit our housemaids at once.”

“I’ll engage,” said Lady Rafford, assuming an air of unwonted self-importance, “I’ll engage this would-be-fashionable Miss Vulgarity could not acquit herself, though she were here, so well as one of my waiting-maids.”

“O !” said Lady Dominant tartly, and with some haste, “0 let us be done with this poor – empty-headed but aspiring cotton-spinning [-16-] Miss; the very idea of listening for one moment to her application is perfectly monstrous.”

Miss Manchester was of course refused a ticket, there being no one but the Baroness to support her claim. Neither would she but for the circumstance that her brother, who has since married Miss Manchester, had so urgently pressed her to do so.”

Check out Grant’s account of Almacks here.

Here are some reviews of Almack’s when it opened:

London, Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, Volume , 1891

To view a voucher and learn more, check out this blog: https://www.regencyhistory.net/2015/01/a-genuine-almacks-voucher.html

Pingback: Seen Over the Ether: A Novel About Almack’s « Jane Austen’s World

Pingback: Seen Over the Ether: A Novel About Almack’s « Jane Austen’s World

Pingback: Seen Over the Ether: Regency Hot Spots « Jane Austen’s World

Pingback: Seen Over the Ether: Regency Hot Spots « Jane Austen’s World