Don’t you hate it when media gives the modern age credit for all the black eyes on humanity?! As if violence, crime, and other social ills were proprietary to contemporary culture.

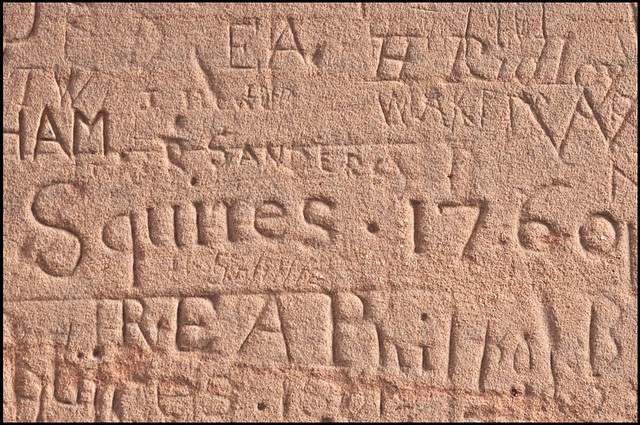

On one of my many year abroad late night tramps across the Midland country side, one of our favorite haunts was Kenilworth Castle.

What still resonates with me, many moons later, is the graffiti etched into the walls of this beautiful ruin. Instead of modern epitaphs or gang script homages, the vast majority of graffito posts were little status updates from the Georgian-Victorian era.

Graffiti has been around since the beginning of man. Greek graffiti in Roman buildings has been discovered, Roman graffiti in long gone cities found and decoded, and even some cave drawings are up for debate as a type of graffito (for the term, from Italian, essentially means scratchings or scribblings on walls).

But just as we might not place much significance in spray painted symbols in our contemporary cities, its arguable the actual words of graffito have much to say about the culture of their time period.

In 1859, Punch featured a satire of the recently published Graffiti of Pompeii. In the account of Graffiti of London, a fictional character named Sir Cannibal Tattoo arrives in London from New Zealand and “pottering about the ruined streets of the abandoned metropolis” notes graffiti in his sketchbook and tries to determine their meaning.

“Sir Cannibal found inscribed BR GS SNA S Briggs is an Ass. Now who was Briggs and who the bold Satirist who thus unhesitatingly summed up his character in an epithet? We find no mention of Briggs in any History of England and are half inclined to risk the idea that the name was given generically to the class of pseudo sportsmen and athletes depicted in the celebrated Leech Cartoons now in the Presidential Museum at Wellington.

In the same neighbourhood Sir C Tattoo perceived written the well known NO P PE Y No Paupery which shows that even in those barbarous times people were beginning to see the absurdity of being poor while anybody else had aught to be deprived of. The inscription NO P PERY occurs in numerous parts of Old London especially near the churches founded by St Posey which is a proof that the alms given away by these imitators of Catholicism had failed to satisfy the laudable ambition of the working classes for independence.

On a door near the New Gate of London which was also the place of execution for by a fine conception our ancestors thrust the polluting scene of death extra mania or as far from the heart of the City as possible Sir C Tattoo found a rude representation of the instrument of execution the Gallows and of a figure pendent there from Beneath was written MANNING. This was the work of an illiterate person and obviously was meant for Man Hung such being the brief heading which the newspapers of the day gave to an account of one of the events common and ludicrous in those times but which happily are now of rare occurrence and which plunge our Republic of Islands into mourning when such an example has been necessary.

A little further and on a piece of pavement was clearly to be read I AM STAR IN G but what this means or what the speaker was staring at we have at present no conception. It might however have been the facetious answer to the celebrated British caution Mind Your Eye.

Sir C Tattoo suggests that a letter has been dropped and that the word should be Starting. But what could such an inscription mean upon a pavement? The riddle must we fear remain unsolved in smculo satculorum.”

Punch is essentially making fun of reading too heavily into historic graffito by having their character imbue much meaning on commonplace scrawlings.

“At another point and near what is said to have been the residence of the London Mayors before their extirpation is found a rich distich I M TH KN F HE ASTL ND YOUR A D TY R 8CA. This there is great difficulty in reading and a difference of opinion has arisen as to the filling up of the destroyed letters. The best scholars Sir C Tattoo says are inclined to this reading I am the Knife which the Aatley Hundred your A Dirty Rascal.

There is evidently some City legend or sarcasm conveyed in this couplet. The place where it was found was the banquet hail of the Mayors and probably some Astley a negligent servant is charged with having presented to his master your Mayor to cut his venzon a knife wet with the flesh of turtle fish the favourite luxury of those demi savages.

But there is scope for a score of treatises on the subject. The last word of the first line has been interpreted Castle and though we do not think this correct it may have alluded to the Elephant and Castle the famous white bait house which stood near the Bank and was frequented by its managers. A pretty couplet about which there is little mistake records on a window sill that My love Sal is ap gal the defaced word being no doubt portly the English girls or gals being celebrated and admired for their fat.

In another place is DO OUR M THER NOW BE U perhaps the affectionate yearning of children Do, our mother note return to us or Does our mother now remember us.”

In the Monthly Magazine in 1801, Sir Richard Phillips wrote of Brussels and the “mischief” of vandalism which, although thankfully “has not extended its ravages to the Aristrocratic part” was much marred by theft of artifacts from Churches and other acts of vandals.

What is most interesting about the history of graffiti, particularly as scholars in the Regency era began noting its anthropologic significance, is that it appears to be a very human need or instinct to give voice or bear witness when an individual has no other opportunities to do so.

This would be particularly significant in a more spatially constrained society, where graffiti might be used to directly address neighbors, friends and enemies. Today, we might go abroad into virtual communities. The practice of digital graffiti, or variations of flaming, bashing, trolling, essentially offer trolls opportunities to give voice where they might otherwise be suppressed/repressed.

Evidently, virtual or physical vandalism in the form of graffiti has long been a behavior of marginalized populations. In an increasingly literate world like the Regency, words scrawled on an edifice could incite, tease or otherwise “flame” spatially constrained communities.

No doubt, as Sir Phillips assures us, this would have not been common in Aristocratic areas with the exception of non-residential destinations like Kenilworth Castle. More likely, as is true today, graffiti would have occured in public places or lower class domiciles where renters, rather than owners, occupied its interiors.

Undoubtedly, intent of the graffiti would have some factor in determining its location (as is also true today) depending on the intended audience.

But as evidenced in Punch’s satire, these messages out of time and context, are not as relevant as the ever-present need for the others to contribute to the human dialogue.

Pingback: Browse On By: What I’m Loving This Week « Sweet Rocket