Its a great time of year to go to the theater. Depending on your region of the world the blustering, frigid weather eliminates all possibilities for activities al fresco and pushes us indoors. For a bit of culture and entertainment, the theater rarely disappoints. Not only do the players on stage entertain, but its a fabulous place to rub elbows with other citizens and people watch.

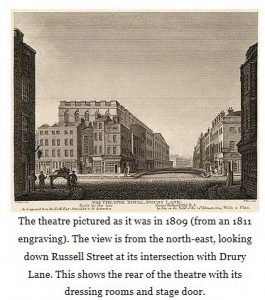

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane has existed in four different physical manifestations in the same site since 1663. Several fires, including one in 1809 that burned the third and supposedly “Fireproof” theater resulted in the final fourth iteration completed in 1812.

Richard Brimley Sheridan, who was part owner and writer (noted for humor) for the Theatre Royal in 1809 was reportedly in the House of Commons when news of the conflagration created uproar. According to sources “The House of Commons…voted an immediate adjournment when the disastrous news arrived; though Sheridan himself protested against such an interruption of public business on accountof his own or any other private interests. He went thither, however, in all haste, and whilst seeing his own property in flames, sat down with his friend Barry in a coffee-house opposite to a bottle of port,coolly remarking, in answer to some friendly expostulation, that it was “hard if a man could not drink a glass of wine by his own fire!” ( ‘Drury Lane Theatre’, Old and New London: Volume 3 (1878), pp. 218-227. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=45148)

The Theatre Royal, with a seating capacity of over 3,000, was designed by Benjamin Dean Wyatt on behalf of the committee led by Whitbread, opened on 10 October 1812 with a production of Hamlet featuring Robert Elliston in the title role. Shakespeare was a popular playwright for the theatre, with playbills demonstrating the high volume of the bard’s works performed there. (For a collection of plays from 1808 check out this book and for a collection of playbills from 1815 check out this book)

According to Boyd Hilton (in a Mad, Bad & Dangerous People) Shakespeare reepresented the Regency “culture of Dissent”; Coleridge saw him as an “authoritarian hero-worshipper” while Cruickshank loved his subversive humanity and “hatred of arbitrary power and cruelty.” Hilton goes on to argue that the actors themselves represented this “theater of politics and politics of theater” with “political connotations of different styles of acting–the statuesque authoritarianis of John Philip Kemble…as against the naturalistic but melodramatic histrionics of his younger rival Edmund Kean.”

Theaters themselves, Hilton suggests, were overt in political leanings with Covent Garden productions supporting Tory governments and the Theatre Royal opposing with a Whig perspective.

The theatre was an acceptable passtimes for many walks of life, and where the pit would indeed mingle in some proximity to the Ton. Furthermore, the theatre was one of the few places where the upper echelon would depend on lower classes for entertainment.

That being said, no matter the enjoyment of the theater being enacted on stage (and indeed off stage), the ultimate impetus of this cultural attraction was storytelling through entertainment about cultural moreways and folkways. If marriages were contracted, assignations made and political coups hatched, then this was simply a by-product of assembling so many characters under one roof. While television is mostly driven by consumer culture, movies remain a very strong current mode of gathering individuals under the guise of entertainment.

Personally, I vastly prefer the theater as an experience, for the spark of life and truly thought provoking material now presented in small playhouses does surpass most modern cinematic screenings.