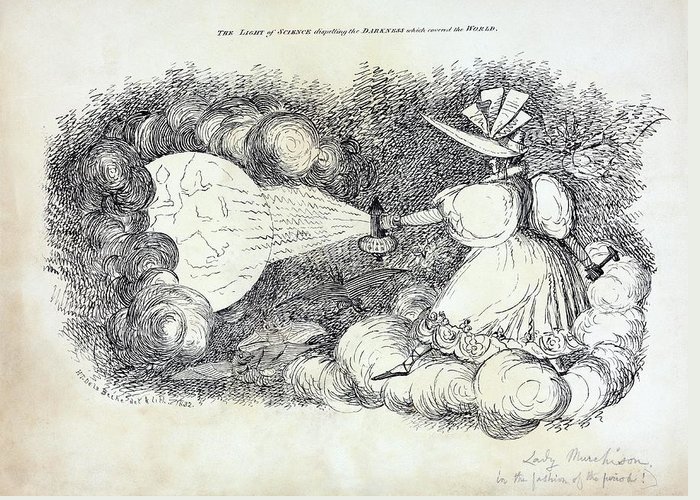

The light of science’. This satirical cartoon by Henry T De la Beche, from 1832, depicts the light of science dispelling the darkness which covered the world. It shows Lady Murchinson, wife of the Scottish geologist Sir Roderick Impey Murchison (1792-1871) holding the torch.

I will admit that I torture myself with social media. Doomscrolling, mostly, but for some reason I have gotten into the habit when I am reviewing of popping over to GoodReads to see what other reviewers have said. I started doing it to catch any CW when I started adding those to reviews, but its become another form of torture more oft than naught.

Take my recent review of My Fake Rake. I loved that book so much, that I wanted to check my bias at the door and so looked at other reviews.

One in particular tore down the sex positivity and then said something to the effect of it was unrealistic for dozens of trained female scientists who publish papers and go on expeditions to have existed in the Regency era.

I am consistently mystified where readers get some of the information about “historical accuracy.” Yes, its been a theme of the blog the last year, and yes I realize its often less about accuracy and more about something else. Racism, sexism, ableism…all the isms under a label of “accuracy” and “history” which make historians, even amateur ones like myself, cringe.

So I started this series, Representing Regency, to offer counterpoints when I see this garbage claim about historical accuracy. Because, I have receipts. Receipts in the form of actual history. And the funniest thing is that with a simple Google, this reader could’ve discovered just how far back women academics have existed: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_female_scientists_before_the_20th_century

In my Regency Women of Character posts, I have tried to introduce Regency Readers over the years to the variety of women doing fantastic, hard, and fascinating things during the early 19th century. This has included scientists, academics and philosophers including: Engineer and inventor Sarah Guppy, pioneering paleontologist Mary Anning, religious thought leader Hannah More, writer and reformer Sarah Trimmer, and adventurer and businesswoman Lady Hester Stanhope.

But I am happy to introduce some other lady nerds from the early 1800s. I focused on British born and/or operating scientists, but if you check out the Wikipedia link above there is a veritable treasure trove of links to other women across the world.

Charlotte Murchison (nee Hugonin) was a geologist, married to geologist Roderick Impey Murchinson, whom she traveled with throughout Europe on rock hounding expeditions. With a significant collection of fossils, Charlotte contributed to the discipline with detailed sketches which appear in many of her husband’s publications. Charlotte opened up lecture theatres at Kings College London to female geology students and did all of these great works while suffering malaria (https://trowelblazers.com/charlotte-murchison/). Charlotte and Mary Anning are the subjects of the upcoming film Ammonite.

Frances Stackhouse Acton (nee Knight) was the daughter of noted botantist Thomas Andrew Knight, who supported her education and own work as a botanist, archaeologist, writer and artist. One of her most exciting discoveries was a Roman villa beneath her husband’s Acton Scott Hall. She had diverse interests and membership in various societies.

Mary Morland Buckland was a paleontologist, marine biologist, and scientific illustrator who used her honeymoon as an excuse for a year long geological tour of Europe. In between raising nine children, she focused on her interests (despite a sexist husband) and education in her local community. When her husband passed, she continued her own research beyond the illustrations from his publication. Her fossil reconstructions are held within the Oxford Uni Museum of Natural History. Her illustrations and specimens were also utilized by George Cuvier, the “founder” of paleontology (https://scientificwomen.net/women/buckland-mary-171).

Maria Elizabetha Jacson was a writer and botanist who mostly published anonymously. However, one of her books was recommended by Charles Darwin himself: “But there is a new treatise introductory to botany called Botanic dialogues for the use of schools, well adapted to this purpose, written by M. E. Jacson, a lady well skilled in botany, and published by Johnson, London.[” You can read the book online here.

Anna Maria Walker (nee Patton) teamed up with her husband Col. George Warren Walker who made extensive collections and observation son plants in Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon). She is best known for her contributions to the study of orchids. Read more about Anna here.

Elizabeth Andrew Warren was a marine algologist and Cornish botanist who organized a network of plant collectors for the Royal Horticultural Society of Cornwall, and worked with a variety of scientific societies despite no formal higher education. She was a founding member of the Royal Cornall Polytechnic Society, discovered several new species of plants, and developed A Botantical Chart for the Use of Schools (https://www.royalcornwallmuseum.org.uk/making-her-mark-in-a-mans-world-botanist-elizabeth-warren).

Mary Somerville (nee Fairfax) was a polymath and scientific writer who mostly focused on maths and astronomy and was the first female member (jointly with Caroline Herschel) to the Royal Astronomical Society. Her obituary called her “the queen of science” and she published a variety of papers including studies of light and magnetism. It was her work that led to the discovery of the planet Neptune. Mary was also active in the women’s suffrage movement (https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/10871422/mary-somerville-google-doodle-today/).

Caroline Hershel moved from Germany to England with her brother, astronomer William Herschel, in 1772 and served as his general assistant. Mastering algebra and astronomy on her own, she became one of the first women to receive a salary for scientific work. In the late 1700s, she discovered 8 comets, 14 nebulae, and compiled a supplemental catalogue for star clusters. In addition to being the first female member (jointly with Mary Somerville) to the Royal Astronomical Society, she also received many awards and accolades.

Mary Anne Whitby (nee Symonds) was a writer, artist, and an expert on the cultivation of silkworms responsible for reintroducing sericulture to the UK in the 1830s.

Elizabeth Fulhame was a chemist who invented the concept of catalysis and discovered photoreduction. She wrote numerous essays, one book which was translated into German, and was well received by British academia.

Sarah Sophia Banks collaborated with her botanist brother, Joseph Banks, and was an avid coin collector which is now held by the British Museum and Royal Mint.

These are just some examples, along with the ones we have previously posted about, about the amazing women doing scientific research and publishing in the UK during the Regency era. Its not hard to imagine the multitudes more that have been unsung through the annals of history because of sexism. Many women published anonymously, because of the stigma attached to work and women scholars. It was also not uncommon for the men in their lives to get much of the credit for their labors.

There is no doubt there was sexism at play during the Regency prohibiting formal and university educations for most women, keeping them out of societies and other opportunities, but there is significant evidence that in spite of these odds stacked against them, lady scholars were still prolific and critical to a variety of disciplines.

I would also point out that My Fake Rake didn’t feature dozens of published female scientists. Those portrayed were self-taught and self-aware of the limitations on women at the time. Its exhausting that even this, portrayals of brilliant women taking the crumbs left to them, is suspect. Its also part of what has made academic and professional life so difficult, even today, for women like me. Lady nerds.

So, Regency Readers, I hope I have delivered a counterpoint that shows women were actively being published, going on expeditions, and making tremendous discoveries that helped their respective disciplines during the Regency era.

Thank you!!!!

Lovely! I’m currently working on a new book and was inspired by the Herschel siblings.