Thank you for the question, Curious Lady, and for being a Regency Reader!

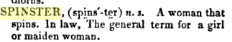

The term spinster was the general term for an unmarried woman. The male corollary was and is bachelor. The pejorative “ape leader” could be applied to both sexes to indicate an unmarried state (Farmer, 1909). Ape leader derived from “The Taming of the Shrew” and represented the punishment of old spinsters to lead apes in hell. This term was well in use during the publication of Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1823).

Johnson, S. (1828). A Dictionary of the English Language. Germany: Robinson.

Johnson, S. (1828). A Dictionary of the English Language. Germany: Robinson.

The term spinster comes from the late 14th century, from when unmarried women were expected to spin as an occupation. It became adopted as the legal designation for unmarried women starting in 1600 until the 1900s. There was no age attached and generally, the term is used in many primary sources as a neutral term. There seems to be some connotations, as a woman aged, when spinster became more of a “woman who will never marry” and therefore counter to cultural norms, but it wasn’t always implying an older woman or a woman unmarriageable.

Marriage was particularly important for women in the 19th century, because her fortune was tied up in marriage or men. It was very difficult for them to exist without the support of men (and remember, its only in the middle of last century many Western women became able to open up their own checking account, for example). Thus, spinsterhood as a final state was a blight (Hufton, 2002).

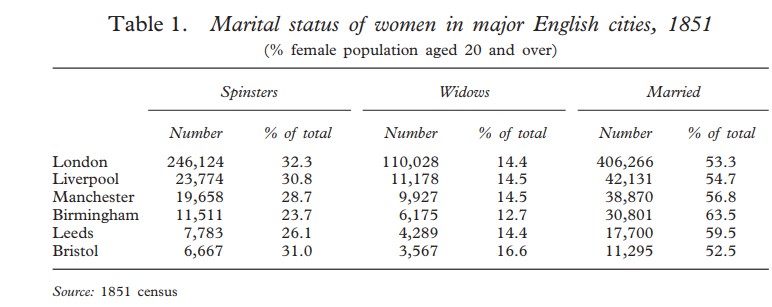

Green and Owens (2003) share data from 1851 that shows urban English marital status of women, demonstrating that while marriage was the norm, it was not out of the realm of commonality for women to be spinsters. This chart focuses on women over the age of 20, which is relevant to other research. Many of these women were engaged in domestic service, and while many would eventually marry, their research shows that if they had not by the age of 30 or 35, they were likely to never do so (there is another chart in their article, but out of respect for copyright I will not publish).

Ansell (1874) did detailed demographic research and uses the terms spinster and bachelor consistently to describe unmarried women and men. The peak age of unmarried women seems to have been between 21 and 28, with the most occurring between 21 and 25.

There were many pejoratives for unmarried women by the Regency including “old maid” and “ape-leader” (Spinster, Old Maid, Or Self-Partnered-Why Words For Single Women Have Changed Through Time – UMBC: University Of Maryland, Baltimore County). Going on linguistics, UMBC confirms that a mid-twenties was the age in the 17th century that a single woman became an old maid. Esobar (2003) recalls that in the Victorian era, if women were not married by their late twenties, they were considered “on the shelf” regardless of the fact that statistics do not support this assumption.

As for the term “on the shelf” the record is less clear. I have found a poem from 1877 that references a fifty year old spinster “long ago laid on the shelf” and a few other uses in prose from around the same era. I haven’t found any relevant usage from newspapers in the Regency years, and if we look at Google ngram, the peak usage is really in the 1960s and 1980s. The idiom is thought to date to around the 17th century, when books were stored on shelves and if they were seldom used they would be placed on higher shelves to be forgotten. If anything, it doesn’t seem to enter mainstream parlance until after 1820, and even then its usage was usually for inanimate objects not unmarried women.

Most of the signs point to this term, with reference to a spinster, being used most commonly in the Victorian era. As such, it’s not a phrase we feature in the Regency Cant resource due to its dubious origins.

Hope this answers your question! If you have found earlier primary references to “on the shelf”, please leave a comment below!

Ask us more questions about the Regency in our Regency ? page. We are also trialing a new service, Research Requests, for writers or others wanting a more in-depth answer with sources, or looking for a Beta read with an eye to historical details.

Appreciate our research? Please share with other readers, leave your comments, buy a book through one of our links on reviews, or buy us a cup of tea!

Ansell, C. (1874). On the rate of mortality at early periods of life … and other statistics of families, in the upper and professional classes. United Kingdom: (n.p.).

Escobar, K. E. (2003). The Victorians’“Unclaimed Dividend”: A Literary Study of the Middle-class Spinster. Baylor University.

Farmer, J. S. (1909). Slang and Its Analogues Past and Present: A Dictionary … with Synonyms in English, French … Etc. Compiled by J.S. Farmer [and W.E. Henley]. United Kingdom: Harrison & Sons.

Green, D. R., & Owens, A. (2003). Gentlewomanly capitalism? Spinsters, widows, and wealth holding in England and Wales, c. 1800–1860. The Economic History Review, 56(3), 510-536.

Hufton, O. (2002). Women without men: Widows and spinsters in Britain and France in the eighteenth century. In Between Poverty and the Pyre (pp. 148-177). Routledge.

Johnson, S. (1828). A Dictionary of the English Language. Germany: Robinson.