Regency Reader Question

I began to wonder about the term Corinthian as described in Georgette Heyer’s books. It seems to have become a part of the Regency Canon but I could not find any historical basis for this extremely positive interpretation – Green’s online dictionary lists most contemporaty mentions as referring more to a rakehell, or a “young buck” someone going on wild sprees etc. I saw your definition matches that of Heyer’s Corinthian heroes but do you have any contemporary source to support that it is not a part of Georgette Heyer’s imaginary Regency reality? Thanks!

| Source of Question | Research |

| Additional comments | My interest is from being an amateur translator for Heyer’s books to my native Hungarian, for family amusement only. Hungarians being largely unfamiliar with the Regency of both history and fiction, many terms require explanatory footnotes which I’d like to be factually correct. |

Thank you for the question and for being a Regency Reader! I think this is an insightful question with a complicated answer.

Corinthian, as defined on the website: “Corinthians were athletes, sportsmen who excelled in most sporting activities of the day including fencing, boxing, hunting, shooting, driving and riding in addition to be always well dressed and mannered gentlemen (https://www.janeausten.co.uk/bucks-beaus-dandies/).” Our official definition, based on primary sources, in Regency Cant emphasizes the sporting element as the main distinction between Corinthians and other names for men (including rake). A buck, also defined by primary sources, was a debauchee or fashionable man bent on pleasure who also was a sporting type, so in a sense a similar appellation to Corinthian. Young buck simply implies a younger man of the same.

The term Corinthian to imply a well-dressed sportsman was employed by contemporaries in the 19th century, so definitely not a Heyerism.

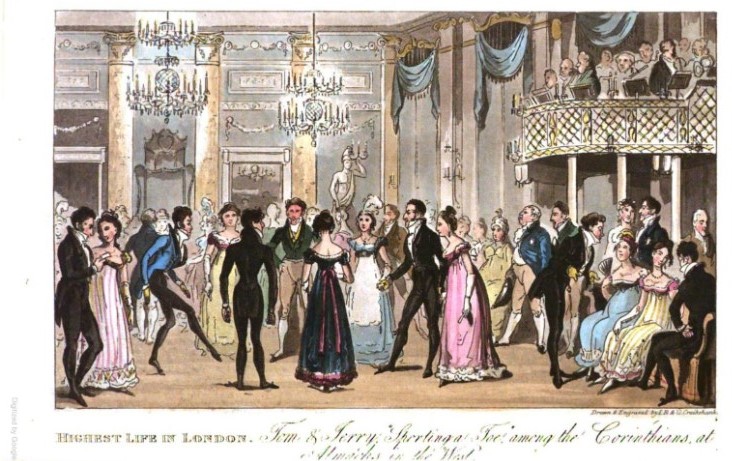

Egan and the Cruikshanks have a whole satire book entitled: “Life in London Or, The Day and Night Scenes of Jerry Hawthorne, Esq., and His Elegant Friend Corinthian Tom, Accompanied by Bob Logic, the Oxonian, in Their Rambles and Sprees Through the Metropolis” which includes this plate:

The caption is a bit hard to read at this scale, but reads “Tom and Jerry “sporting a Toe” among the Corinthians at Almacks in the West. Here, Corinthians are elegantly dressed gentlemen in the style of Brummel . The Corinthians appear respectable, acceptable, and dancing on attendance at the ladies.

The whole book (illustrated by Cruikshank) is the story of elegant Corinthian Tom, escorting his country cousin Jerry (along side the rakish “Oxonian” friend Bob Logic) as they explore London in order to offer Jerry a bit of Town Bronze.

Corinthian is also used, in this book, to describe a female character which is counter to other references but is likely what a lot of Regency romance writers term a “fast” woman.

This website offers a map of their adventures and shows all the plates, which are simply delightful slices of life in late Regency England: Mapping Pierce Egan’s Life in London (1821) – Romantic London

Egan was a well known sportswriter, and some of his fictional tales focused on fictional famed sportsmen, which he called Corinthians. While there is an element of the rakehell in Egan’s depiction of the Corinthian, the focus really was on being a high status, sports focused gentleman.

Carver posits that Robert Cruikshank, inspired by his Nabob brother in law’s return to London and the subsequent London tour, commissioned his brother George for a set of prints depicting London life. Egan was conscripted to provide the narrative, due to his “unparalleled knowledge of the sporting set and underworld” (Carver, p. 2). Tom and Jerry are depicted attending a variety of events including fashionable tonnish activities, sports (including less savoury ones), and then doing some less fashionable activities like drinking gin and visiting rookeries.

Carver argues that Corinth, during the 19th century, was a synonym for an immoral city (Corinth used to be a centre of “fashionable whoredom”) or a city noted for luxury and licentiousness which when applied during the Regency was meant to be a generic term for a rake.

Generally, the term when applied to architecture or furniture or design was meant to capture a Grecian origin or look, after the island of Corinth, that had a distinctive ornate style of architecture. It was used frequently in these fields in the late 18th century/early 19th century to describe Grecian columns or other features. Corinthian brass was of particular note, and there was speculation in the Georgian slang dictionaries (see below) that this is the origin of the term Corinthian as applied to a brazen fellow.

Here are the definitions commonly used for Corinthian in the Georgian era:

The new and complete dictionary of the English language (1795)

And here are some 18th Century slang definitions:

A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785)

The 1785 definition was repeated in the 1811 definition found in Lexicon Balatronicum.

The emphasis on sporting really was a package deal with Egan, and would be well established into the Victorian era when yachting in particular took up this mantle. This sentiment is echoed in an etymology dictionary of slang published in 1874 (The Slang Dictionary: Etymological, Historical, and Anecdotal):

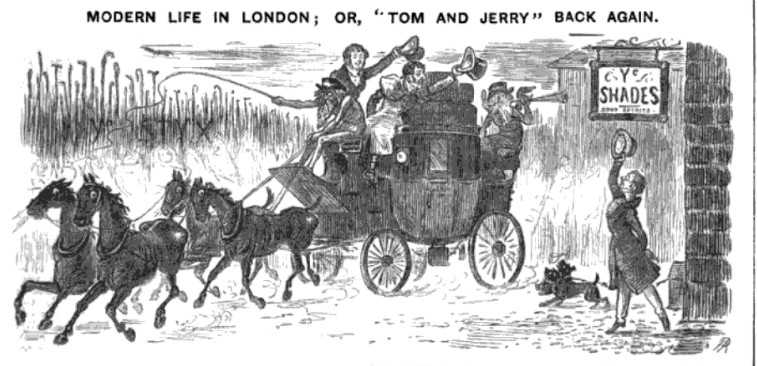

Punch 1882

Its important to note that Corinthian, buck, and rake were slang terms. And like other slang terms, they were variations on a theme of a type of gentleman with similar meaning. Its also important to note that the term was not used in polite society generally because it was cant, so it was more likely to be an appellation one bloke gave another.

In conclusion, I suggest that the two definitions are not mutually exclusive. The Corinthian was an elegant, well dressed and sporting mad rake. The sporting element was introduced with Egan, in the 1820s, and would become the predominant association afterwards.

I want to address the concept of Heyerism/sanitization that I think is implicit in your question and how that might impact a translation. Keep in mind, I am not an expert so these are just my observations.

Heyer, although problematic in other ways, did not generally write about the rakish side of her main characters; sex work/mistresses were generally an uncommon element of a Heyer novel. So did she sanitize the term Corinthian? Perhaps? Without doing a dissertation amount of research on the term and how it evolved, its difficult to say whether or not, at the time she was writing, she knew of the implications of the term and employed it as a subtle hint to suggest the Corinthian was a rake about town.

And I am not sure the definition frequently understood today, or Heyer’s depiction, has a value (like positive) attached to it. The titular character of The Corinthian gets stinking drunk within the first few pages, escapes his duties, and runs away with a minor. The hijinx that ensue are wild and help snap an otherwise bored “swell” out of his funk via the power of love. However, even though he is redeemed in the end, here is a very three dimensional character painted in, often times, unflattering lights.

Does Heyer mention the less savoury habits of the average Corinthian of the era, like talk about him visiting brothels or engaging sex workers? Nope. Does this suggest a sanitized version of a Corinthian? I am not convinced. I think, as with Egan’s depiction, there are things unsaid in these representations (Egan’s work was criticized by contemporaries and the Victorians as immoral) that depending on your lens, you may or may not see.

When I think of Heyer heroes, I assume most have done some raking because I am reading in between the lines a bit but also because my knowledge about what the average gentleman got up to in this era. Heyer loves an older, insufferable hero suffering from ennui after Town has worn him down. One of the world weary aspects, I think, comes from that idea that they have seen and done everything. Even Freddy (Cotillion), who often seems very stupid, has hints of depth which suggest he is in the know even though he doesn’t reveal all. I would suggest the rakishness is implied, although not explicit to avoid Victorian or 1930/40s era moral standards.

So for the purposes of translation, you might want to qualify Corinthian as “an elegant, fashionable, and sporting mad rake.”

Hope that is helpful!

Carver, Stephen. Life in London from Egan to Dickens: Regency Innocence versus Victorian Experience. Dissertation. Retrieved: stephen.pdf (d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net)

Gregory Dart, ‘Flash Style’: Pierce Egan and Literary London, 1820–28, History Workshop Journal, Volume 51, Issue 1, SPRING 2001, Pages 180–205, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/2001.51.180

James, L. (2010). From Egan to Reynolds: The Shaping of Urban ‘Mysteries’ in England and France, 1821–48. European Journal of English Studies, 14(2), 95-106.

Lansbury, C. (1976). Sporting Humor in Victorian Literature. Mosaic, 9(4), 65.

A Corinthian is well-dressed but not a dandy. He is fit and athletic, and especially skilled with horses, both riding and driving.

I had confused the term often over the years I’ve read Regency, so this post was nicely informative and thought provoking. I love the Heyer book, The Corinthian. I love Heyer in general, especially those stories where the older, jaded, sometimes bored Hero snaps out of his ennui because of the heroine.

I’d read the moniker Corinthian used in multiple definitions by the same author (Marian Chesney, e.g.) which really got confusing until I read more and more.

How interesting that your Hungarian reader posed this question. I’m not surprised that Regency fiction is of interest to her, because I keep reading of more and more countries where readers are big Jane Austen fans. I am also not surprised that her friends and family know little of that time-period. If any of them kept a love of history into their adult years it might only have been Hungarian history, or Hungary’s role in history of the last 100+ years because of Europe wide, world wide involvement in the wars. As an American school girl in the 60’s I never learned anything about the Regency. At any rate, she sounds like a fascinating person! Best of luck to her.

Pingback: Regency Pastimes: Monkey Baiting and the Westminster Pit – Regency Reader

wow, thank you for this very detailed answer. There’s a great deal of instructive information and primary source which are especially delightful. I haven’t read Egan’s work but I saw several of the Cruikshanks pictures. It does seem to me that the rakehell/brothel-visiting element was very strong in the earlier sources you mention (the classics-derived meaning directly connected to brothels and courtesans) and the sporting element came into it around the Life in London. I very much like the Grose (1823) definition of “the highest order of swells”. Certainly this is a definition that fits into Heyer’s world even if we look at the completely immoral incarnation of Corinthian, Freddy’s counterpart Jack Westruther – or the other end of the spectrum, the philanthropist Sir Waldo (The Nonesuch) who is annoyed at being accused of rakishness and of sprees and roystering. Thanks again, I appreciate your research!

Thank you for the really interesting question. I am a fan of etymology, so this gave me an excuse to do some digging. I also really appreciate your amazing work to translate Heyer for family and friends!