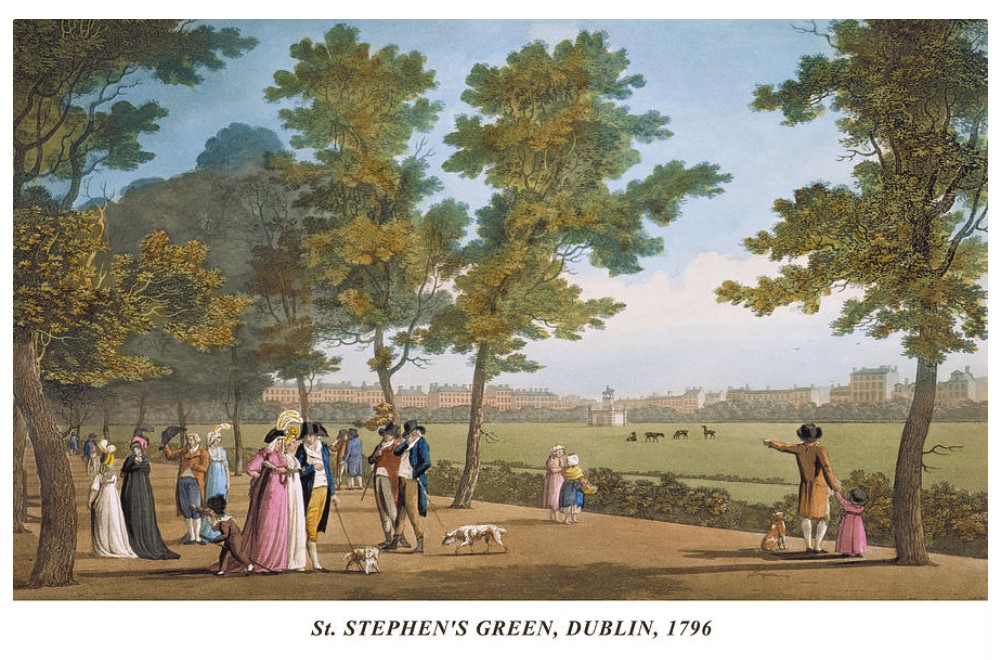

When I sat down to write The Charmer Without a Cause, I thought I knew the basics of Irish history. I’m a proud Irish American who has visited Ireland multiple times, participated in family genealogical research, and read lots of historical fiction about Irish Americans (in fact, in the first grade I wrote one of my first-ever stories about an Irish girl who came over to New England as a maid). I expected to turn to the history books as a matter of fact-checking, not learning-whole-new-things.

However, my series The Prestons takes place during the British Regency, and it turns out most of that historical fiction I read started around the potato famine of the 1840s. Which means I had a lot of research to do!

For all of those Regency Readers who also love Ireland yet don’t really know what was going on with it during our main time period, here is an overview so you can get up-to-speed to the 1820s with me!

Population

The Irish population grew rapidly in the Georgian and Regency periods. One study showed a leap from 2 million people in 1730 to 5 million in 1800, outpacing the growth of the rest of Europe (Hughes and MacRaild). Another datapoint shows up to 6.8 million people in Ireland by 1821 (Gibney).

That said, the population was very young. In 1821, 41% of the population were children under the age of 15. There were more people on the island under the age of 20 than adults between the ages of 20-60 (Hatfield p.11). Talk about being outnumbered!

The British authorities considered education an important part of their strategy to “anglicize” the Irish children (more on that later). In 1810, one official took a survey in South Munster and found that 4 out of 5 common Irish people could not speak English, and 49 out of 50 could not write their own names (Hatfield p. 67). That said, as of 1821, 560,000 Irish children were reported to be attending primary schools, including “hedge” schools that assembled anywhere they could, including hedges (Gibney).

Among the wealthier Irish people – including the English landlords – it was “fashionable” to be a Francophile. There was an obsession with French clothes, goods, books, and wine (Hatfield p. 101). Meanwhile, the unhappier rural and working classes looked to French politics for inspiration of overthrowing a monarchy. This includes inviting the French to join in the 1798 rebellion and invoking Napoleon’s name in their own political songs!

Local Government

The country was divided into counties, with grand juries as the administrative body overseeing governance of each county. These grand juries usually consisted of 23 of the wealthiest or most powerful men in the county; the majority were Protestant. Note that eligibility was based on property ownership, not residence. So a gentleman with property in Ireland could get appointed to the grand jury deciding local matters even if he spent the rest of the year in London. Getting selected for the grand jury was a major status symbol, and people got offended if they weren’t appointed or even if they weren’t listed in the right order in the newspapers.

The grand juries met twice a year for assizes: once during Lent in the spring (March or April) and again in the summertime during a season called Lammas. Villagers usually gathered to greet and/or jeer at the jury members as they arrived in town for the session.

During the assizes, the grand juries oversaw duties including:

- Deciding which cases went to trial

- Setting annual county taxation rate

- Deciding county spending and infrastructure investment

- Hiring county officials

- Funding gaols and hospitals

Those county officials they hired included:

- Secretary (chief communicator)

- Treasurer (to collect “cess” aka tax and pay contractors)

- Conservator (road inspector and county surveyor)

- Gaoler

- Clerks for the courts

- Interpreters for Irish speakers

Economy

Some of the main industries of nineteenth century Ireland included textile production, such as linen in the north, shipbuilding, distilling and brewing, and agriculture (Irish Times).

With the Act of the Union, the British had more control over the economy and started investing in building highways and canals to industrialize the Irish countryside. However, with the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Ireland suffered an economic slump, which was only worsened by a potato blight in 1816 and a typhus epidemic (Gibney).

Religion

As most people know, religion has been a pressure-boiler issue for Ireland for centuries. The majority of the Irish population did not convert to the Anglican Church when Henry VIII threw off Catholicism. Since then, the Irish Catholic population had backed several attempts to put Catholic leaders back on the throne, as well as fomented revolutions to take back their own political power.

The majority of the Irish population was Catholic. The political power resided in the hands of the Protestant members of the Church of Ireland, an outpost of the Anglican church. Meanwhile, there were also sizeable communities of Presbyterians, and of course, there were minority communities as well.

Because of the history of warfare between Catholics and Protestants in Ireland, the British government enforced laws that essentially made Catholics second-class citizens. At the turn of the nineteenth century, they could not hold long-term leases, vote in elections, employ more than two apprentices, or establish their own schools or colleges (Hatfield p. 55)

On top of that, there was bad blood and discrimination against people based on religion. The Protestants in power generally believed that Catholic adult society was superstitious with a combination of worshiping the Virgin Mary, hosting exorcisms, and still believing in fairy beliefs. Meanwhile, they considered Catholics bad parents and wanted to use education to teach the children to be “civilized.” One Protestant observer characterized the Catholic community as “crowded gaols, ferocious turbulence, habitual sloth, gloomy bigotry” (Hatfield pp. 56-60).

Evangelical missions in Dublin targeted reform against drinking, gambling, and popular literature. Bible societies focused on children, disabled, Irish-speakers, and prisoners. In general, there was a culture of the minority religion holding political power and considering the majority religion inferior (Hatfield p. 65).

Politics

Ireland’s political relationship to England changed drastically in the midst of King George III’s reign. After a major rebellion in 1798, the Irish parliament was dissolved and Ireland was absorbed into the “United Kingdom.”

Prior to 1798, Ireland was subordinate to England with its own parliament made up of Irish-titled peers. Ireland had been subjugated to England since the Treaty of Windsor in 1175, which meant there was no recent memory of Irish independent leadership. On top of that, English monarchs created Irish peerage titles to reward Englishmen and exert more control over Ireland, especially as religion became a major divide between the Irish people and the English rulers. By 1798, there were so many Irish titles that when 150 peers didn’t show up, there were still enough peers there to hold the Irish parliamentary session.

In 1798, the United Irishmen, led by Irish-born peers and upper class Irish elite, launched a bloody rebellion against English rule. After the rebellion was quashed, England responded with the Act of Union. This dissolved the Irish parliament, bringing Ireland under the English parliament’s rule. In theory, this was billed as helping Ireland, since England was so superior that they would be able to provide better economic measures, infrastructure investments, and general government oversight.

In reality, Ireland’s political power was curbed even more than it already had been: only 28 peers out of hundreds were admitted into the English House of Lords. On top of that, leading Irish politicians – like Lord Castlereagh, later the leader of the English House of Commons – agreed to the Act of Union expecting it would lead to Catholic emancipation. However, King George III refused to grant any rights to Catholics after the act was passed, leaving many in Ireland feeling duped. (Castlereagh resigned in protest.)

In the aftermath of the Act of the Union of 1801, then, Ireland was trying to find its way as a new political identity. The English rulers were wary of any hints of rebellion, remembering all too well the violence of the 1798 uprising. Meanwhile, the Irish people across religion and classes were feeling out a new situation that left them feeling more powerless than ever.

It turns out that Ireland in the Regency period had a lot going on! I loved incorporating this research into my novel, The Charmer Without a Cause, and I look forward to returning to Ireland in future projects!

The Charmer Without a Cause

Everyone knows that a happy marriage begins with a lot of money and one good lie…

When Benjamin Preston falls in love with Lady Lydia Deveraux at first sight, his family thinks this is the start of yet another of his failed courtships. Benjamin is almost as surprised as they are when Lydia encourages his attention and even agrees to marry him. His family suspects she is after his newly-inherited ten thousand pounds, but Benjamin holds out hope that at last he has found his true love.

Lydia can’t help finding Benjamin attractive. After all, he is handsome, kind, and compassionate. But her heart belongs to Ireland – and to an Irish rebel who died for the cause of freedom. Now Lydia is determined to marry for wealth and political influence so she can help free Ireland from Britain’s rule.

Even if that means trapping Benjamin in a loveless marriage.

As their courtship progresses, Lydia and Benjamin find themselves caught in a web of lies, plots, and unquenchable lust. The only question is: can they help Ireland without breaking each other’s hearts?

About Katherine Grant

Katherine Grant writes award-winning Regency Romance novels for the modern reader. Her writing has been recognized by Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Awards, the Next Generation Indie Book Awards, the National Indie Excellence Awards, the Romance Slam Jam Emma Awards, and the Shelf Unbound Indie Book Awards. If you love ballgowns, secret kisses, and social commentary, a book hangover is coming your way. Find out more at www.katherinegrantromance.com.

Sources

A Short History of Ireland by John Gibney

Growing Up in 19th Century Ireland by Mary Hatfield

Ribbon Societies in 19th Century Ireland by Kyle Hughes and Donald MacRaild

Ireland’s Industrial Heritage from the Irish Times

Irish Grand Jury System from Longford Library